Why is all of this just a moo point on education?

On Flagship Schools, Observing Development, and the Rarity of Talent

“I think I may say that of all the men we meet with, nine parts of ten are what they are, good or evil, useful or not, by their education.”

― John Locke, Some Thoughts Concerning Education

Last week, I commented on Taman School’s Instagram post about Flagship Schools (Sekolah Unggulan). The basic premise of the post was this: just because someone gets accepted into an elite school doesn't mean they’re guaranteed to become a "person", a well-rounded, capable individual. Once you’re in, you still have to work hard for it. In one of my pinned posts, I’ve written something along those lines.

What caught my interest, though, was one of the comments under that post. In essence, it argued (implicitly) that a flagship school should be about turning “ordinary” students into “extraordinary” ones, instead of filtering people out with many tests and requirements.

I found that perspective genuinely interesting. It got me reflecting.

So I wrote this newsletter to share my thoughts and why I think that, while all of this is valid, it still amounts to a moo point at the end of the day.

Let’s begin.

I - Ivy League and Its Modus Operandi

I want to start by addressing the comment on that post.

If flagship schools are meant to turn average students into superstars, how would they maintain their perception of prestige?

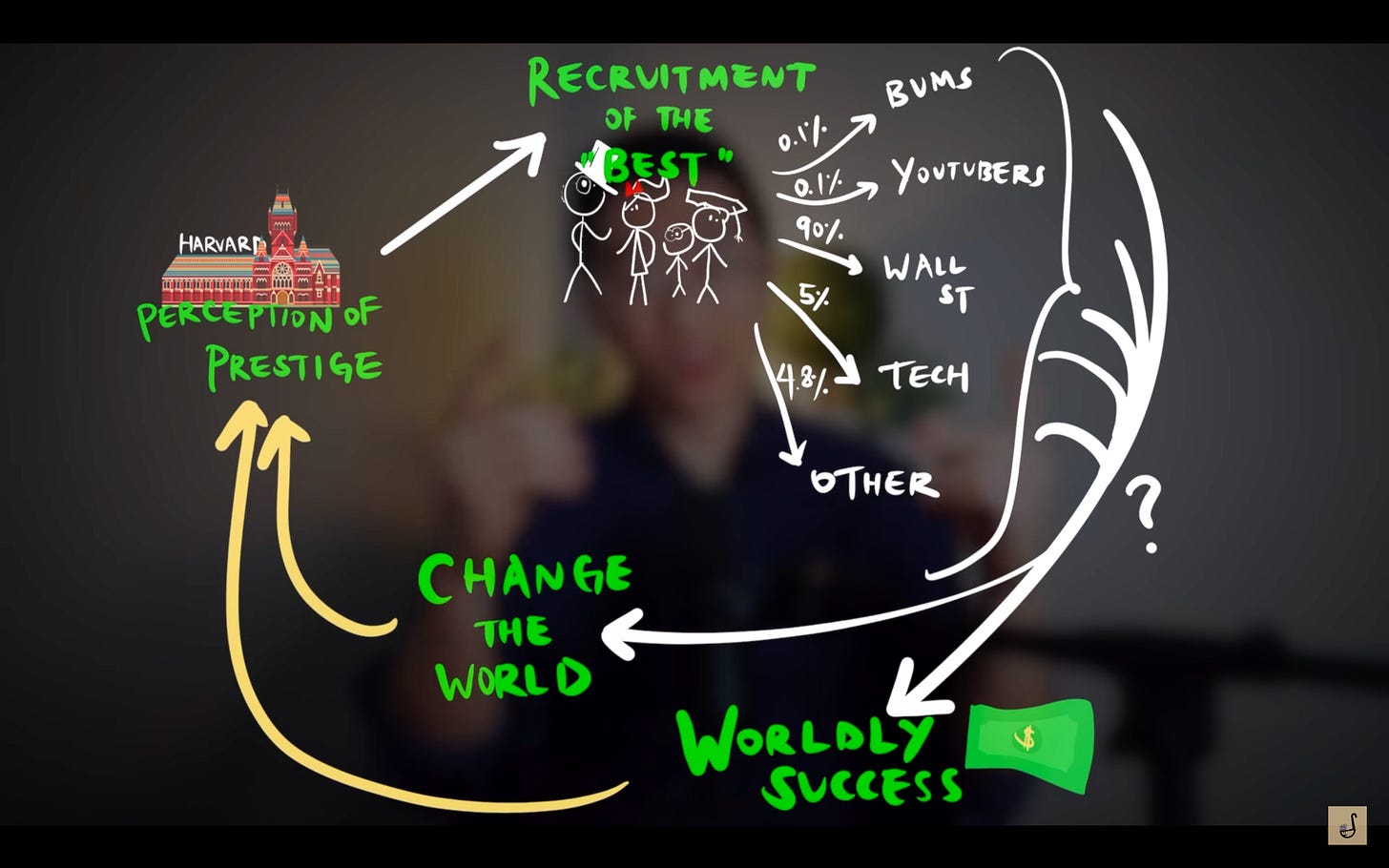

What many people don’t seem to realize is that flagship schools are built to maintain a specific image, one tied to excellence and competence. This image naturally attracts some of the best teachers and students in the country. Because these individuals are already strong in what they do, they tend to produce real-world success. Whether it's getting into even more prestigious institutions, landing jobs at multinational companies, or winning major competitions, their achievements strengthen the school’s reputation. It becomes a reinforcing cycle.

If you have some time, I recommend watching a video that explores this further through the lens of the Ivy League. But to put it simply, most people who get into Ivy League schools don’t necessarily need those schools to succeed. In fact, it's often the schools that benefit more from the association with those individuals.

That’s why the task of a flagship school, in practice, is more about picking winners rather than developing one.

To clarify, I’m not making a value judgment here. I’m simply describing how these institutions work. But if you believe that flagship schools should serve a different purpose, perhaps returning to the 1994 vision introduced by former Minister of Education and Culture, Wardiman Djojonegoro, then there are a few challenges you will likely face.

He introduced the concept of “Sekolah Unggul” with the hope that Indonesian students could reach national and international levels of achievement. That vision still holds value. However, the real challenge, in my view, is not primarily structural. It lies in the more technical aspects of human development, which fall within the domain of psychology itself.

II - Causal Opacity in Development

Many technical problems fall within the domain of psychology that relate to development. One of them is the problem of causal opacity. Causal opacity is defined as when the relation between cause and effect is not necessarily visible, or basically opaque to the observer. This opacity exists because most constructs in psychology are latent, meaning they cannot be directly seen or measured. Instead, we rely on proxies; indirect indicators that we believe adequately represent the underlying construct. From these proxies, we then operationalize the construct, turning it into a psychological measurement that can be used in research and practice.

This problem is important to our discussion because when talking about a flagship school as a place where one fully develops their potential, it first starts with the assumption that school affects students in the first place. But if how that effect plays out in real time is not observable, then how can we really determine what causes it?

It’s best described in this passage from the book, Talent and Society: New Perspectives in the Identification of Talent:

Suppose we could locate that sleepy boy in the back row, the potential poet; what would we do for him? Would we offer him a liberal scholarship to one of our better private schools? Would we ‘enrich’ his curriculum with special readings in poetry, or in the Greek classics? Or would we perhaps excuse him from school requirements altogether on the ground that he would do better as a self-educated man? Or would we supply him with a vocational counselor who would help him find his real niche in life? These are not silly questions. The plain fact of the matter is that we do not know what we would do; we do not know enough about what goes into the making of a poet. We may know somewhat more about what goes into the making of a scientist or a professor (based on I.Q. tests and academic training); but we still know far too little to be confident about how to develop talented performance out of talent potential.

At the present stage of our knowledge, to identify the real ‘comers’ is only the preliminary step to understanding why they are promising. Suppose, for example, by a series of really massive explorations of test items correlated with various criteria, we were able to construct a test which inevitably pointed to the promising young person. And suppose further, as is often the case with contemporary psychological tests, it would be extremely difficult to understand why a given item on the test had the connection it did with future success. Suppose, in short, that the instrument worked, but that we had no idea as to why or how it worked, or what the problem of talent development really involved—in other words, that we had no theory. We would be able to identify talent potential without understanding its nature or the process by which it develops.

What advantage would such an instrument be to us? What should be done with the gifted students it identified? Certainly, there would be no lack of advice. Perhaps it would not be their congressmen writing to the ‘comers’ telling them to keep their mouths shut, but it would certainly be somebody—if only the psychologists and educators—telling them what to do. The chances are, however, that any special educational ventures would spoil some of the talent potential, since in our hypothetical example it would have been identified from validity coefficients based on allowing students to develop normally in the previous generation. If careful control experiments were performed to uncover just what educational procedures decreased the validity coefficients of the tests, we might, after generations, begin to learn something about the kinds of education which favor the development of talent.

But the whole orientation of such an approach is wrong. It places far more emphasis on talent potential as a fixed attribute of a few people than we have any reason to suppose is true. Rather, talent potential may be fairly widespread, a characteristic which can be transformed into actually talented performance of various sorts by the right kinds of education. If so, the emphasis should shift from identifying talent potential to studying the process by which talent becomes actual, by which it develops. Such a focus requires above all a knowledge of theory—an understanding of what we are measuring, how it develops under different circumstances, and how it is related to the ultimate criteria of talented performance which we want to predict. Until we achieve these goals, our ignorance of the process by which talented performance develops will remain an outstanding gap in current talent research. (p. 23 - 25)

This specific point is key:

The emphasis should shift from identifying talent potential to studying the process by which talent becomes actual, by which it develops. Such a focus requires above all a knowledge of theory—an understanding of what we are measuring, how it develops under different circumstances, and how it is related to the ultimate criteria of talented performance which we want to predict.

Why a theory? To explore unknown terrain, you need a map to guide you. That’s where theory comes in. It allows us to navigate territories that are unobservable at first by forming hypotheses and testing whether they offer a parsimonious explanation for the related phenomena. And if we manage to develop a talent development theory (TDT) that proposes a mechanism to turn potential into actuality, we might have a shot at this.

III - The Rarity in Talent

Another reason why developing a theory is crucial in the context of talent development is that, contrary to popular belief, talent is actually quite scarce. Most people are far too optimistic about the prevalence of exceptional individuals, especially those who are gifted across multiple dimensions.

In the paper, The Number of Exceptional People: Fewer Than 85 per 1 Million Across Key Traits, Gilles E. Gignac addresses this very misconception. The study explores how cognitive biases often lead us to overestimate how common it is to find multi-talented people, especially in high-stakes contexts like recruitment or elite education.

Using data simulated from a multivariate normal distribution (N = 20 million), the study focused on three core individual difference variables (intelligence, conscientiousness, and emotional stability), which are commonly associated with strong real-world performance. These variables were modestly correlated (ranging from -0.03 to 0.42), and the results were eye-opening:

Around 16% of individuals were classified as notable (at or above the average on all three traits),

Only 1% met the remarkable threshold (≥ 1.0 SD),

A mere 0.0085% were exceptional (≥ 2.0 SD), and

Just one person in 20 million qualified as profoundly exceptional (≥ 3.0 SD).

These findings drive home the point: people who are exceptional across multiple traits are incredibly rare. So when McClelland and others talk about "constructing a test which inevitably pointed to the promising young person," we have already built such tests. But the issue remains the same.

We end up only “identifying talent potential without understanding its nature or the process by which it develops”. And not only would a TDT help solve this problem for the exceptional few, it would also benefit those who are not particularly intelligent, low on conscientiousness, or may even struggle with emotional stability. Because at the end of the day, the process of developing oneself should not be reserved only for the exceptional.

From here, there are two important issues to consider.

First, from a talent management perspective.

I once asked a friend, who was about to pursue a Master’s in Industrial and Organizational Psychology, a specific question:

If talents are indeed rare, doesn’t that imply that most organizational teams will inevitably include non-talented members?

That leads us to an even more intriguing question:

How do groups that consist mostly of non-talented individuals still manage to produce extraordinary results?

This question has been at the heart of research in group dynamics. Several lab studies have found that average ability is the most consistent predictor of group performance.

However, other studies challenge this view. They argue that average ability might not be as critical as other factors, such as social perceptiveness (also known as emotional intelligence), skill diversity, and cognitive style diversity.

In other words, what makes a group effective might not be the presence of individual brilliance, but how people think, relate, and collaborate across differences.

Second, from an education policy standpoint.

There’s a tweet that captures this tension quite well:

The tweet juxtaposes two different types of education policy goals a country can pursue.

On one hand, you can prioritize nurturing exceptional talent, which might lead to a trickle-down effect through innovation, breakthroughs, or transformative leadership. This approach might produce Nobel laureates, trailblazing entrepreneurs, or groundbreaking researchers if successful.

On the other hand, you can prioritize raising the average, focusing on ensuring a minimum standard of competence for every citizen. This might mean guaranteeing universal basic skills, ensuring everyone finishes high school, or offering free access to English classes. It all depends on the kind of competencies a country wants its average citizen to have.

IV - It’s a Moo Point

To wrap up our discussion, it’s time to show why, while everything I’ve written above may be true and filled with interesting ideas, it is nonetheless a moo point.

In a podcast, Bagus Muljadi, a professor at the University of Nottingham and host of Chronicles, once noted that the problem with Indonesia’s education system is that it is neither here nor there. The policies are inconsistent and often contradictory.

One example he gives is this: if education is treated like a commodity, where attending university requires students to pay, often at a premium, shouldn’t citizens then have the right to sue a university if, after graduation, they are unable to get a job? He’s pointing out that if education is commodified, there must also be some form of accountability, either from the state or from the market.

Another example comes from a speech by Nadiem Makarim, where he claimed:

“We are entering an era [when] degrees no longer guarantee competence, graduates do not guarantee readiness to work and contribute, accreditation does not guarantee quality, and attending classes does not guarantee learning.”

In the introduction to his book Education and Political Participation (Edukasi dan Pelibatan Politik), Agus Suwignyo comments:

“The quoted statement from the Minister of Education above may be “true” in terms of its substance, but it should not be used as justification to underestimate formal education.

An academic degree is indeed not a guarantee of someone’s professional competence because professional competence can only be demonstrated through relevant job performance, not through an academic title or a piece of diploma. However, it would also be inappropriate if we then glorify job competence as the sole benchmark of educational success.

Will the government decide that schools and universities no longer need to issue diplomas as a sign of student graduation? Are job providers (including the government) willing to give opportunities to anyone without degrees/diplomas to demonstrate their competence as a replacement for the administrative selection process in employment recruitment? Take an example directly related to the Ministry of Education and Culture: the recruitment of teachers.

In teacher recruitment, is the government willing to disregard the academic degrees/diplomas of applicants and focus solely on their competencies? For instance, could anyone who feels competent as a teacher, without needing to show a diploma, be immediately accepted to teach at a school? Then, a selection could be held based on their teaching performance—without considering degrees and diplomas. Would the Minister of Education dare to test his own statement that “degrees do not guarantee competence” in something like teacher recruitment, using such a method?”

In truth, I suspect they wouldn’t. Because the system still runs on credentials, on formal markers of education, even when we’re told those things no longer matter.

Lastly, in another podcast, Prof. Stella Christie, Deputy Minister of Higher Education, Science and Technology of Indonesia, argues that universities should not mandate students to write a thesis that must reach 100 pages. She states that these procedures end up adding no real value to the content. She cites examples such as Einstein’s general relativity paper, which was only nine pages long, and top journals that publish impactful research in just a single page. This leads her to question whether requiring 100 pages is truly necessary.

This raises an important point. According to the Regulation of the Minister of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology No. 53 of 2023 on Quality Assurance in Higher Education:

Article 18, Paragraph 9 states that undergraduate and applied undergraduate programs may assess student competence through a final project that can take the form of a thesis, prototype, project, or other equivalent forms, either individually or in groups.

Article 19, Paragraph 2 requires master's and applied master's programs to assign a final project in the form of a thesis, prototype, project, or other equivalent forms.

Article 20, Paragraph 3 states that doctoral and applied doctoral students must complete a dissertation, prototype, project, or other equivalent form.

These legal foundations support the idea that a thesis does not need to be 100 pages long. So, if such flexibility already exists, wouldn’t the most effective step for a Deputy Minister be to actively communicate this to universities or even “nudge” them in that direction? Why let the message stop at a podcast? Why not take concrete actions to implement these ideas systemically?

From here, I think you can sense what I’m trying to get across. We see an inconsistency between the kind of vision that our government preaches and the kind it actually practices. Why is that?

It’s because the inconsistency is by design. Not in the sense that it was meticulously planned from the start, but rather something that has been embraced as a response to the social, political, and economic conditions in Indonesia. Given the country’s vast diversity, inconsistency allows policymakers the flexibility to accommodate the various interests of different groups and communities.

While one might think that catering to different interests is trivial, it actually serves an underrated but vital purpose: keeping society stable. Too much consistency can lead to rigidity, which may not fit the unique needs of certain communities and can even lead to conflict, or in the most extreme cases, civil unrest.

This is why the contradictions, particularly in the educational sector, still persist to this day.

Is there a solution to this issue? Not quite. From a policy standpoint, any major paradigm shifts will likely lead to backlash and end up being revised within the next cabinet ministry. This has happened repeatedly to our national curriculum, for example, the long-standing system of high school specialization (penjurusan IPA, IPS, dan Bahasa), which had previously been removed, is now being reintroduced starting in the 2025/2026 academic year. I'm reminded of a paper from 2007 that illustrates this point quite clearly:

“Since the first educational curriculum (the 1947 curriculum) until now, there seems to be a degeneration in the main objectives of educational activities. Among other things, the practice of education has become increasingly superficial, failing to consider aspects of urgency, substance, and implementation. As a result, it is likened to a disease: treating the head when it is the foot that is in pain; of course, the illness will not be cured (Nasrullah, 2006).”

We've been dealing with the same old problem all over again.

Truly, a moo point.