How to establish a "Regime of Truth"

Indonesia's Minister of Culture Rehashes the Debate on Sexual Violence of May 1998

Editorial note: This essay is written with a heavy heart. While I draw on Michel Foucault’s “regime of truth” concept, I do so in response to a troubling and recurring pattern. The recent denial of mass sexual violence during the May 1998 riots by Indonesia’s Minister of Culture echoes the same arguments made by officials between June and December 1998. This is not merely a matter of differing historical interpretation. It is intellectually dishonest to claim that these events did not happen simply because they are not found in official history books, especially when the government is in the process of rewriting the official national narrative.

This kind of rhetoric is not only wrong, but it also reflects a deeper moral cowardice. It is a chilling demonstration of how power can erase pain. As a citizen, I expect better from those entrusted with our national memory.

“I think the biggest tragedy, greater than the ruin of the economy and the political disorder is our lack of morals [budi pekertil as a people who clearly allowed savage [impolite, biadab] behavior toward those equally human. The issue of rape and looting is much bigger than the obvious fact we have the same citizenship and is far removed from the racial friction of the Dutch East Indies and Indonesia. How could we act toward other humans in that way? How could we allow torture, rape, and murder of other humans?”

—Wimar Witoelar (1998) cited in Siegel (1998)

1. What Did the Minister of Culture Actually Say?

In a recent interview, the Minister of Culture, Fadli Zon, was asked whether the sexual violence during the May 1998 riots, especially against Chinese-Indonesian women, would be included in Indonesia’s official history. His response raised serious concerns. He cast doubt on the existence of these crimes by saying, “Is there any hard evidence? Show me. If there is mass rape, who says so? There has never been proof. That is just a story. If it's true, then show me.” He added that such events are not mentioned in history books, and concluded that this kind of “rumor” does not solve any issue. He emphasized that the version of history the government wants to promote is one that can “unite the nation” and that the “tone has to be like that.”

From this exchange, several troubling implications emerge. First, the Minister explicitly denies the sexual violence of May 1998 on the basis that it lacks “proof.” Second, he implies that including these events in official narratives would destabilize national unity. Lastly, he bases this dismissal on the absence of the event in history books, books that his ministry is in the process of authoring. This circular logic reveals a dangerous effort to rewrite history not by uncovering facts, but by deciding what is socially acceptable to remember.

2. Is the Claim True?

The short answer is no. The claim that there is no historical record of sexual violence during the May 1998 riots is demonstrably false. It is a textbook example of Brandolini's law (or the bullshit asymmetry principle):

The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than that needed to produce it.

It takes very little effort to make a sweeping denial. But it takes substantial time, care, and research to unpack that denial, examine the historical record, and demonstrate why it is wrong. So here is what the evidence actually tells us.

First, the event is mentioned in Sejarah Nasional Indonesia Edisi Pemutakhiran Jilid 6: Zaman Jepang dan Zaman Republik by Marwati Djoened Poesponegoro (emphasis added):

Massa yang semula berada di Jalan S. Parman, Jakarta Barat secara cepat bergerak ke arah Jalan Daan Mogot. Mereka melakukan perusakan dan pembakaran mobil-mobil serta gedung-gedung di sepanjang jalan yang dilalui. Selain itu, terjadi pula pemerkosaan terhadap sejumlah besar perempuan-perempuan Indonesia keturunan Cina. Kerusuhan dan perusakan serupa terjadi pula di kota-kota lainnya, terutama di Solo. Suasana Jakarta pun seperti kota mati, tidak ada kendaraan yang lalu lalang. Namun, di tempat-tempat tertentu, khususnya kawasan pertokoan, aksiaksi penjarahan massa terus berlangsung hingga dini hari. (pp. 669 - 670)

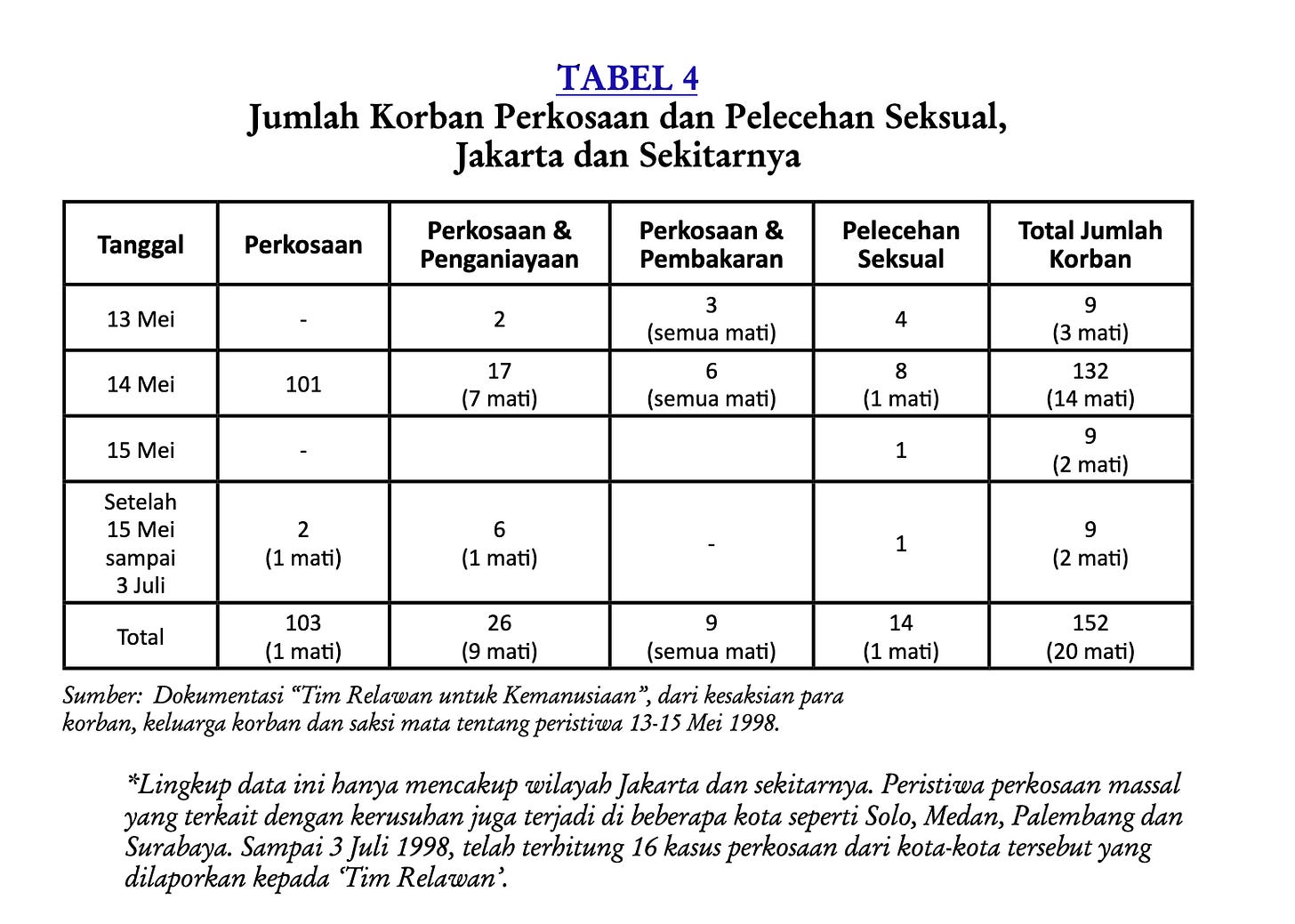

Second, there is the official report by the Tim Gabungan Pencari Fakta (TGPF), a fact-finding team that documented numerous cases of sexual violence, including rape and harassment, during the May 1998 riots.

The team powerfully shows how any attempt to erase or suppress the memory of such a horrific event is not an act of resolution, but an evasion, a refusal to confront the damage done. Forgetting, they argue, does not bring peace. It only prolongs the wound, leaving the nation trapped in cycles of silence and recurring violence. In the section Fokus Pembongkaran: Jaringan Perencana dan Pelaku, they write:

Sesudah kejelasan pola dan bukti peristiwa, ada satu pertanyaan yang tak mungkin diredam: Apa yang mesti dilakukan terhadap jaringan rencana operasi serta perencana pelaku perkosaan massal (dan kerusuhan) itu? Dilupakan, dipeti-eskan, ataukah dibongkar bersama-sama?

“Dilupakan” sama dengan ‘dipeti-eskan’. Tetapi bagimana kita bisa melupakan, kalau apa yang terjadi itu telah menjadi peristiwa yang tak terhapus dari sejarah hidup para korban, keluarganya, kerabatnya, saksi mata, dan ktia semua? Bagimana kita bisa melupakan, kalau peritiwa perkosaan massal dan kerusuhan itu telah membentuk ‘ingatan buruk’ tentang hidup bersama kita : menjadi isi rasa takut dan trauma, depresi dankesepian, keputus-asaan dan bahkan isi imaginasi yang paling hewani dari sekelompok orang? Semua gejala itu sudah merupakan datum (yang terjadi) dari factum (yang dilakukan) dalam hidup bersama. Hidup pribadi dan bersama tidak hanya dibangun dari gaji tinggi atau angka GNP, melainkan juga dari memori, apapun isi dari memori itu.

Dan kali ini, kita sedang berhadapan dengan “ingatan buruk” tentang hidup bersama kita yang berisi peristiwa ‘perkosaan massal’ dan ‘pengrusakan-pembakaran’. Pertama, kami bersaksi bahwa perkosaan massal dan pengrusakan-pembakaran itu sungguh-sungguh telah terjadi. Kedua, kami bersaksi bahwa ratusan korban perkosaan massal dan pengrusakan-pembakaran yang dilakukan secara sistematis dan terorganisir itu adalah bagian tak terhapuskan dari sejarah politik dan cara kita hidup bersama di negeri ini. Ketiga, kami juga bersaksi bahwa perkosaan massal dan pengrusakan-pembakaran itu sama sekali telahmengaburkan (bahkan menghancurkan) perbedaan antara apa yang ‘baik’ dan ‘tidak baik’, ‘beradab’, dan ‘biadab’, dalam kehidupan bersama kita. Dan itulah gejala yang telah menjadi tanda tak terbantah dari kerusakan total kehidupan bangsa kita.

Kalau demikian, maka ‘melupakan’ atau ‘mempeti-eskan’ peristiwa bengis dan massal itu adalah cara kita melarikan diri dari apa yang sudah terjadi. Mirip dengan pati-rasa (pembiusan) yang kita lakukan bersamasama. Sesudah jangka pati rasa habis, yang akan terjadi adalah renteran peristiwa dan tindakan kebiadaban lain. Begitu seterusnya, hidup bersama kita akan dibelenggu dan disiksa oleh rantai kebengisan. Darah kembali tertumpah, renteran korban kembali diciptakan.

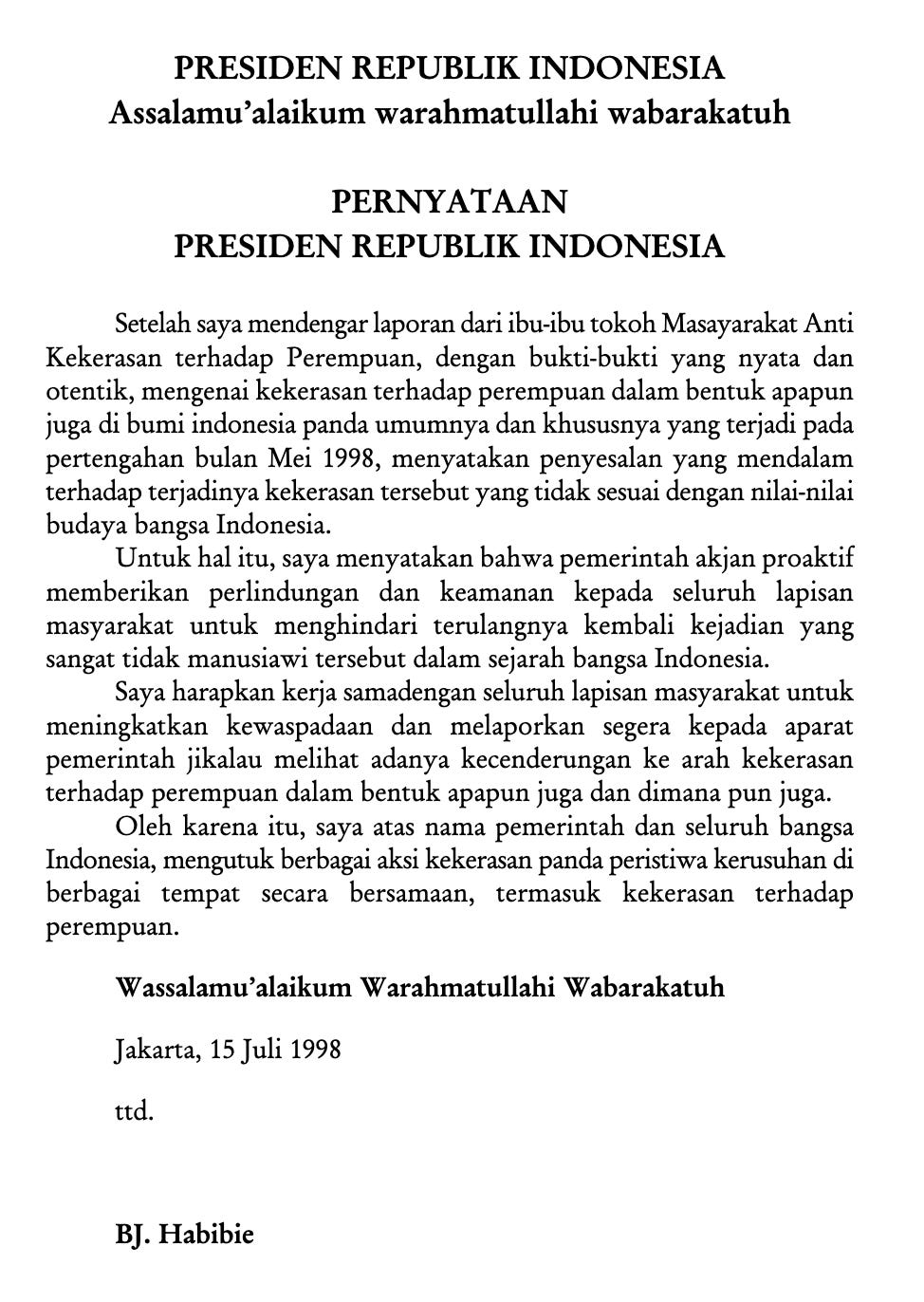

Third, we have the public apology issued by then-President B. J. Habibie, who formally recognized and apologized for the suffering of the victims. Are we to believe that a sitting president would apologize for something that “never happened”? To deny the events today is to imply that Indonesia’s third president deliberately lied, that he coordinated with fact-finding teams, civil society groups, and survivors in a calculated effort to mislead the public. This isn’t just a historical lie. It’s a political absurdity.

Moreover, research on the subject continues to grow. Academic sources such as Gender, Violence and Power in Indonesia Across Time and Space (edited by Katharine McGregor, Ana Dragojlovic, and Hannah Loney) and articles like James T. Siegel’s Early Thoughts on the Violence of May 13 and 14, 1998 in Jakarta and Karen Strassler's Gendered Visibilities and the Dream of Transparency: The Chinese-Indonesian Rape Debate in Post-Suharto Indonesia offer well-documented analyses of the events and the politics of denial.

To argue there is no evidence is, at best, lazy. At worst, it is deliberate disinformation. If a citizen researcher can find this much documentation, the Ministry certainly can too, especially with a 9 billion Rupiah budget allocated for rewriting the official historical narrative. The question is not whether they can. It is why they won't.

3. Should We Be Surprised?

Unfortunately, no. This kind of denial is not new. In October 2024, Yusril Ihza Mahendra, the Coordinating Minister for Law, Human Rights, Immigration, and Correctional Institutions of Indonesia, stated that the May 1998 tragedy did not qualify as a gross human rights violation. The Minister of Culture of Indonesia, Fadli Zon's comments are, therefore, consistent with a broader government effort to downplay or erase the violence.

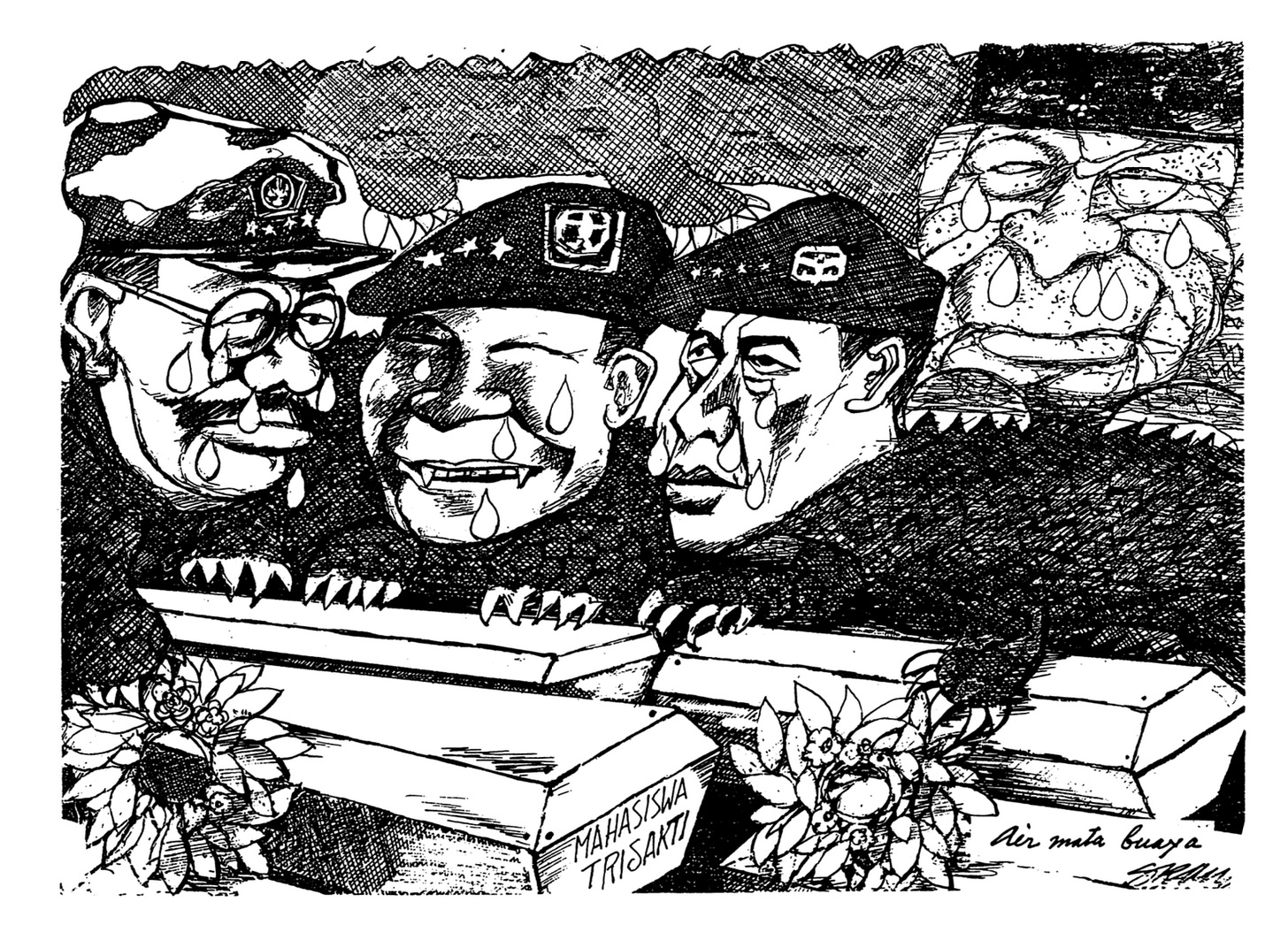

This echoes the denialist rhetoric that surfaced as early as mid-1998, when initial investigations were underway. Despite mounting evidence, key government officials such as the Minister of Women’s Affairs, Tutty Alawiyah, publicly dismissed the reports as “rumours,” only to later contradict themselves by acknowledging “facts” of sexual violence from hospital investigations, before backtracking once again. Lieutenant General Roesmanhadi, the Chief of the Indonesian Police at the time, warned that activists who failed to present conclusive proof could be investigated for spreading lies. General Wiranto, who was then the Commander of the Armed Forces and Minister of Defense, denied that the rapes had occurred, claiming they were baseless rumours lacking any strong evidence. He dismissed testimonies as hearsay, pointing out that most accounts were prefaced with the phrase “katanya” (“it is said”). Activists and volunteers were accused of withholding proof, while government figures used the language of transparency to shift responsibility and place the burden of evidence on victims, many of whom, including the Minister of Women’s Affairs herself, were actively threatened into silence through intimidation and blackmail.

Even the Minister of Justice at the time, Muladi, admitted that while “sociological proof” of rape existed, it failed to meet the outdated juridical standards required by colonial-era laws. Meanwhile, powerful Islamic groups, feeling that the Muslim community was being blamed, framed the accusations as attacks on group identity. This reinforced the “rumour” narrative and relied on familiar tactics to discredit victims by labeling them as prostitutes or politically motivated actors. In this volatile atmosphere, the demand for "proof" became entangled in a politics of visibility and shame. The state’s obsession with photographic evidence created an impossible standard for victims, ultimately silencing them further in a society already saturated with fear, stigma, and surveillance.

Fast forward, the 5-year and 10-year commemorations of the riots were filled with public discourse, from officials and ordinary citizens alike, that sought to cast doubt on the events or dismiss them as rumors. And now in 2025, the state still uses the same tactic. We are debating the same arguments all over again.

4. How Do We Make Sense of This?

Foucault, in his paper The Political Function of the Intellectual, argues that truth is not outside power. Rather, it is produced within power relations and becomes institutionalized through what he calls a “regime of truth.” Each society determines which discourses are deemed true, which are suppressed, who gets to speak, and which procedures are validated as methods for discovering truth. In societies like ours, the truth is shaped by institutions such as education, media, and government.

Truth is of the world: it is produced by virtue of multiple constraints. And it induces the regular effects of power. Each society has its regime of truth, its 'general politics' of truth: that is, the types of discourse it harbours and causes to function as true; the mechanisms and instances which enable one to distinguish true from false statements, the way in which each is sanctioned; the techniques and procedures which are valorised for obtaining truth; the status of those who are charged with saying what counts as true.

What we are witnessing is an attempt by the Minister of Culture to solidify a “regime of truth” in which the mass sexual violence of May 1998 is excluded. By asserting that this violence is not in history books while simultaneously overseeing the production of those very books, the Ministry is effectively designing the apparatus through which truth is recognized. This creates an artificial barrier for regular citizens, who must dig through academic research, old reports, and obscure documents to access the truth.

In Foucault’s terms, this is not a passive forgetting. It is a political strategy, one that limits the production and circulation of counter-narratives to consolidate power and protect institutional legitimacy.

5. Will We Keep Denying These Events?

In her book Berbeda Tapi Setara: Pemikiran Tentang Kajian Perempuan, the first Chair of the National Commission on Violence against Women and a member of Tim Gabungan Pencari Fakta, Saparinah Sadli wrote (based on an article in 2008):

“Meskipun demikian sikap pemerintah dalam era reformasi belum menunjukkan secara konkret kepeduliannya pada pemenuhan hak korban akan kebenaran dan keadilan. Perjuangan para korban tragedi Mei sampai saat ini masih mengalami kendala. Paling terkini, mereka malahan dihadapkan pada respons pemerintah seakan-akan korban tragedi Mei 1998 itu ‘tidak ada.’ Artinya meskipun korban jelas ada, oleh pemerintah dan sebagian masyarakat dianggap tidak ada.”

After 27 years, instead of moving forward, we’ve perfected the art of going backwards. Victims are still waiting for their rights: the right to truth, the right to justice, and the right to reparations. As long as the state continues to deny their existence, it is complicit in prolonging their suffering. The question remains the same: how long will we keep pretending they do not exist?